Success Advice

What Mothers, Musicians & Marshmallows Have to Do With The Science of Success for Extreme Athletes

Over the past century, the science of expert performance has gotten rigorous and codified. Thousands and thousands of experiments have been run; plenty of conclusions reached. Three dominate.

Call them: Mothers, musicians, and marshmallows.

This famed trilogy represent our best ideas about the path to mastery. Yet there’s a wrench in these works: Most action and adventure athletes took a radically different path.

These athletes haven’t just redefined the limits of human potential; they’ve redefined those limits by doing the opposite of what the experts say they should have done. It’s peculiar, alright. Their stratospheric success suggests that we may have completely misjudged the path towards stratospheric success. In fact, it suggests something far more radical: that if we really want to be our best, we don’t just have to rethink the path towards mastery; we need to reconsider the way we live our lives.

But first, the mothers.

In the early 1980s, University of Chicago educational psychologist Benjamin Bloom launched the Talent Project, one of the larger and more thorough “retrospective” studies of expert performance ever undertaken. The Project examined the lives of 120 people, all under the age of thirty-five, all of whom had demonstrated the highest levels of accomplishment in one of six fields: swimming, tennis, sculpture, piano, mathematics, and research neuroscience. The question at the center of the study was: Where does prodigious talent come from, special individuals or special circumstances?

Few of Bloom’s research subjects showed any great promise as children. Instead, the one commonality was encouragement, a lot of encouragement. In each case, there was a parent or close relative who rewarded any display of talent, and ignored or punished the opposite. Prodigies, it seemed, were made, not born. As Bloom later told reporters: “We were looking for exceptional kids, but what we found were exceptional conditions.”

The idea settled an uneasy corner of the nature/nurture debate: It democratized expertise. Provided the right environment and the proper encouragement, it meant that everyone had a shot at perfection.

But many of the athletes involved in action and adventure sports came up the hard way. The wrong environment, little encouragement. “A lot of us were from broken homes,” skateboard pioneer Duane Peters once told the LA Times. “We were freaks and misfits.” And if home life wasn’t rosy, the outside world even less supportive. Twenty-five years ago, skateboarding was a crime; snowboarding was banned at most resorts; and surfing, to quote the always relevant Point Break, was “for little rubber people who don’t shave yet.”

Certainly, there are plenty of action and adventure athletes who came from incredibly supportive backgrounds. Bloom wasn’t wrong — “mothers” matter—but too many of these super athletes came up sideways, backward and feral for this to be the single deciding factor. Something else is going on. And that something else is where the mu- sicians come into play.

Next, the musicians.

In the early 1990s, Florida State psychologist Anders Ericsson performed one of the more famous studies of expertise in recent history. By surveying elite violinists at Berlin’s Academy of Music, Ericsson found that while one’s early environment was helpful, what truly distinguished excellent players from good players from average players was hours of practice. By the time they were twenty years old, expert violinists had put in 10,000 hours of “deliberate, well-structured practice.” The others had not. As Malcolm Gladwell famously explained in Outliers:

“[The] research suggests that once a musician has enough ability to get into a top music school, the thing that distinguishes one performer from another is how hard he or she works. That’s it. And what’s more, the people at the top don’t work just harder or even much harder than everyone else. They work much, much harder.”

But another wrench. If 10,000 hours of “deliberate, well-structured practice” is the secret sauce, consider Shane McConkey’s goals while skiing:

“What I love to do on the hill is find an interesting way to do something fun.”

Put differently, deliberate well-structure practice is a rigorous, compliance-based approach to mastery. It means you crawl before you walk. It doesn’t mean Laird Hamilton surfing Pipeline at age four, or Danny Way in the deep end of the pool at the Del Mar Skate Ranch by seven. In broader terms, deliberate practice is also how we train genius these days. It’s factory athletics. It’s Kumon math tutoring, Baby Einstein, Suzuki violin, et al. But it’s also the world McConkey walked away from. He turned his back on the factory, yet somehow, still went on to become Superman.

Finally, the trouble with marshmallows.

In 1972, Stanford psychologist Walter Mischel, performed a fairly straightforward study in delayed gratification: he offered four-year-old children a marshmallow. Either the kids could eat it immediately or, if they waited for him to return from running a short errand, they would get two marshmallows as a reward. Most kids couldn’t wait. They ate the marshmallow the moment Mischel left the room.

When interviewed fourteen years later, the kids who could wait were more self-confident, hardworking, and self-reliant. Those who resisted at four ended up scoring 210 points higher on their SAT’s at sixteen. This may not sound like that much, but, as fellow Stanford psychologist Philip Zimbardo explains:

“[That] is as large as the average difference recorded between the abilities of economically advantaged and disadvantaged children. It is larger than the difference between the abilities of children from families who parents have graduate degrees and children whose parents did not finish high school. The ability to delay gratification at four is twice as good a predictor of later SAT scores as IQ. Poor impulse control is also a better predictor of juvenile delinquency than IQ.”

But there’s another issue. According to psychologists, by definition, action and adventure athletes are “sensation seekers.” They’re impulsive pleasure junkies. Delayed gratification is not their game.

So what gives? How do a bunch of impulsive hedonists raised far from the storied incubators of athletic excellence end up rewriting the rulebook on human potential? The short answer, of course, is flow.

Psychologists describe flow as “autotelic,” from the Greek auto (self) and telos (goal). When something is autotelic — i.e., produces the flow high — it is its own reward. No one has to drag a surfer out of bed for overhead tubes. No one has to motivate a snowboarder on a powder day. These activities are intrinsically motivating, autotelic experiences done for their own sake. The high to end all highs.

When doing what we most love transforms us into the best possible version of ourselves and that version hints at even-greater future possibilities, the urge to explore those possibilities becomes feverish compulsion. Intrinsic motivation goes through the roof. Thus flow becomes an alternative path to mastery, sans the misery. Forget 10,000 hours of delayed gratification. Flow junkies turn instant gratification into their North Star—putting in far more hours of “practice time” by gleefully harnessing their hedonic impulse. In other words, when it comes to time perspectives, flow allows Presents to achieve Future’s results.

Business

Why Smart Entrepreneurs Are Quietly Buying Gold and Silver

When stocks, property, and cash move together, smart business owners turn to one asset that plays by different rules.

You’ve built your business from the ground up. You know what it takes to create value, manage risk, and grow wealth. But here’s something that might surprise you: some of the most successful entrepreneurs are quietly adding physical gold and silver to their portfolios. (more…)

Business

The Simple Security Stack Every Online Business Needs

Most small businesses are exposed online without realising it. This simple protection stack keeps costs low and risks lower.

Running a business online brings speed and reach, but it also brings risk. Data moves fast. Payments travel across borders. Teams log in from homes, cafés, and airports. (more…)

Business

If Your Business Internet Keeps Letting You Down, Read This

From smoother operations to better security, dedicated internet access is quietly powering today’s high-performing businesses.

Today, a dependable internet service is the bedrock for uninterrupted business operations. Many organizations rely on stable online connections for communication, data transfer, and customer interaction. (more…)

Did You Know

How Skilled Migrants Are Building Successful Careers After Moving Countries

Behind every successful skilled migrant career is a mix of resilience, strategy, and navigating systems built for locals.

Moving to a new country for work is exciting, but it can also be unnerving. Skilled migrants leave behind familiar systems, networks, and support to pursue better job opportunities and a better future for their families. (more…)

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks agoBrandon Willington Builds 7-Figure Business by Ignoring Almost Everything

-

Health & Fitness3 weeks ago

Health & Fitness3 weeks agoWhat Minimalism Actually Means for Your Wellness Choices

-

Did You Know3 weeks ago

Did You Know3 weeks agoWhy Most Online Courses Fail and How to Fix Them

-

Business3 weeks ago

Business3 weeks agoIf Your Business Internet Keeps Letting You Down, Read This

-

Business2 weeks ago

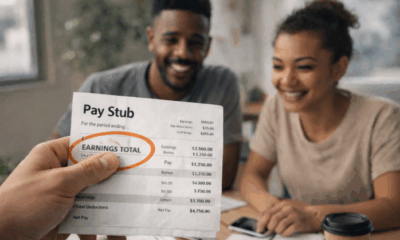

Business2 weeks agoEntrepreneur’s Guide to Pay Stubs: Why Freelancers and Small Business Owners Need a Smart Generator

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoThe Salary Shift Giving UK Employers An Unexpected Edge

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoThe Simple Security Stack Every Online Business Needs

-

Scale Your Business2 weeks ago

Scale Your Business2 weeks ago5 Real Ways to Grow Your User Base Fast

5 Comments